An India-Pakistan War could break British politics

Conflict in South Asia is one of the biggest threats to our domestic security

Could civil war come to Britain? David Betz, Professor of War Studies at King’s College London, seems to think so. In 2023, his essay, ‘Civil War Comes To The West’ Betz paints a bleak picture, of a crumbling civilization which could suddenly erupt into all-out conflict.

Many of Betz’s arguments are both agreeable and frightening. I would strongly encourage you to read his work. As he rightly notes, civil wars are most often caused by a mixture of economic slowdown, distrust in government, and ethnic fragmentation. Thanks to decades of policy failure, Britain is now a society characterised by all three. In particular, Betz notes that “approximately 75 percent of post-Cold War civil conflicts have been fought by ethnic factions”; for decades, we have been busily engaged in importing many of those factions, as part of our national policy of mass migration.

However, the phrase ‘civil war’ evokes particular images, which may not be entirely appropriate for understanding the civil strife which may soon emerge in Britain. ‘Civil war’ conjures images of organised groups, occupying defined territories, and operating as quasi-political actors.

Yet for every civil war which matches this stereotype, there are dozens of low-level ethnic conflicts which manifest themselves in a far more pedestrian fashion. My instinct is not that Britain will avoid disorder in the coming decades; in fact, without a significant change of course, I think that this is almost inevitable. Instead, I suspect that the disorder that we do experience will be less explosive, instead manifesting itself as a kind of persistent dysfunction which underpins every aspect of political life.

What does that mean in practice? Occasional riots, ghettoization, tit-for-tat attacks on places of worship, and a political system dominated by sectarian interests - periods of peace, punctuated by intermittent episodes of violence. We may find it difficult to identify straightforward ‘sides’ to the conflict; groups and individuals on any given ‘side’ may have similar objectives, but may also act independently of one another. Neither should be expect the conflict to be fought along a binary axis; the threat is not ‘Islamists’ or ‘the far-right’, but persistent, low-level ethnic and religious strife. Given our historical insulation from domestic threats of this type, we may not even identify our society as ‘in conflict’ until we have been in such a state for several years.

This kind of low-level ethnic conflict is nothing new. In fact, this is how most modern historians characterise ‘the Troubles’ In Northern Ireland, a thirty-year conflict which blended civil unrest and political deadlock with paramilitary violence, both against the British state and between paramilitaries themselves. The IRA’s bombing campaigns are the most well-remembered manifestation of the conflict, but we ought not to forget the role played by riots, mass protests, communal segregation, and the establishment of temporary no-go areas. This is how most ethnic conflicts look. If such a conflict comes to Britain, an awareness of Ulster’s sorry history will provide a macabre aid in helping Britons to understand the disintegration of their own society.

In keeping with the fuzzy boundaries of ‘the Troubles’, there is little disagreement about the exact start of that conflict. Historians have proposed a number of different dates, including the formation of the modern Ulster Volunteer Force in 1966, the Londonderry Civil Rights March on October 5th 1968, the beginning of the ‘Battle of the Bogside’ on August 12th 1969, or the deployment of British troops on August 14th 1969. This is by no means an exhaustive list.

Likewise, we should not look to identify a single event which will ‘start’ a ‘civil war’ in Britain. Instead, we must be aware of events which might ‘raise the temperature’ - prompting greater intra-ethnic conflict, political deadlock, and social fragmentation. To my mind, the single biggest catalyst for the disintegration of British society would be a war between India and Pakistan.

At first blush, this may seem like an absurd claim. London is some 4,000 miles away from the Indian subcontinent; how could a war between two South Asian countries prompt social unrest on Britain’s streets?

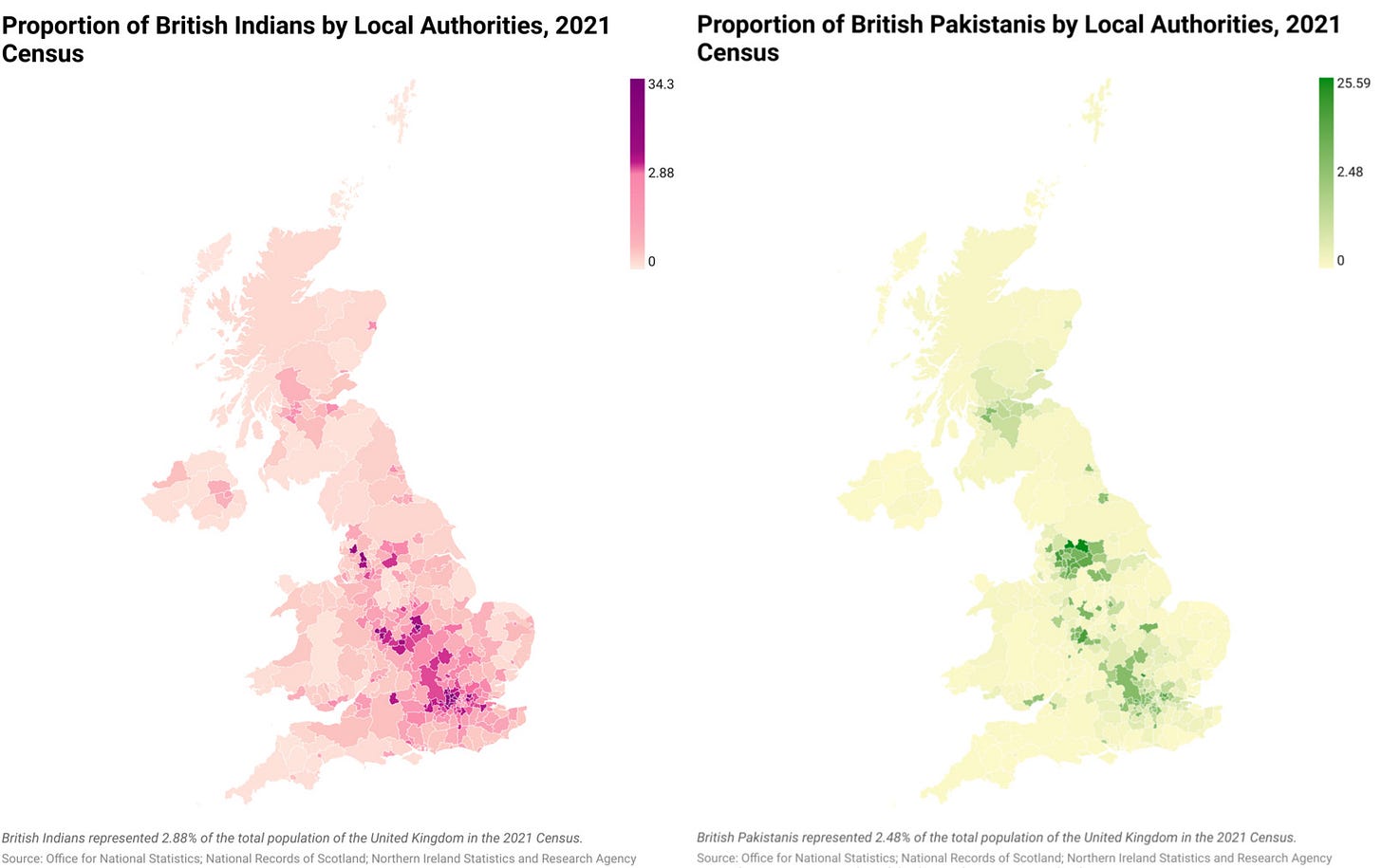

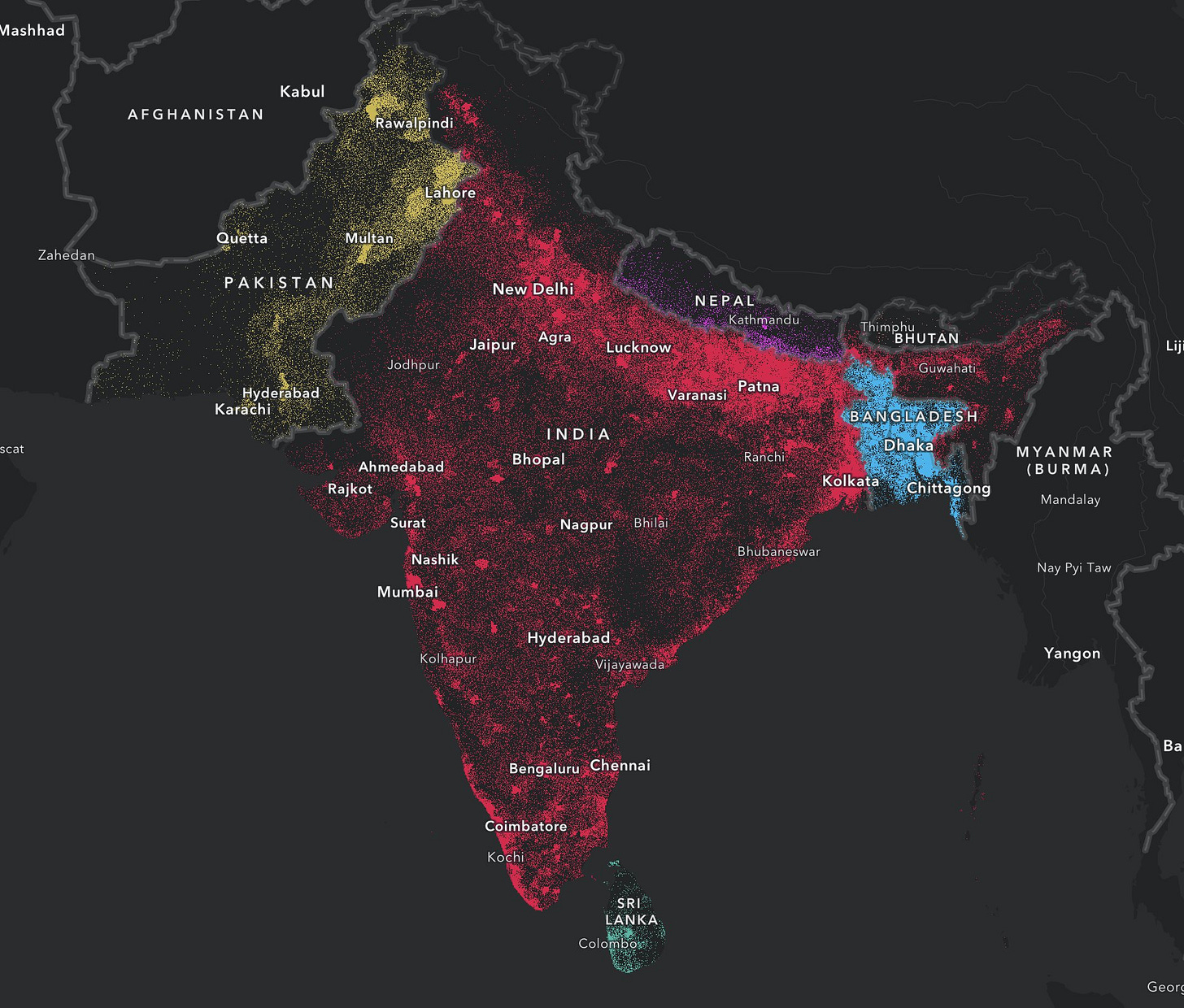

Thanks to decades of mass migration, Britain is now home to millions of Indians and Pakistanis. The 2021 census recorded 1.927 million Indians and 1.662 million Pakistanis living in Britain. Since 2021, migration from non-EU countries has soared, meaning that a further 1 million Indians and 291,000 Pakistanis could be living in the UK as of 2025. By any reasonable measure, these are two of Britain’s most sizeable ethnic minority communities.

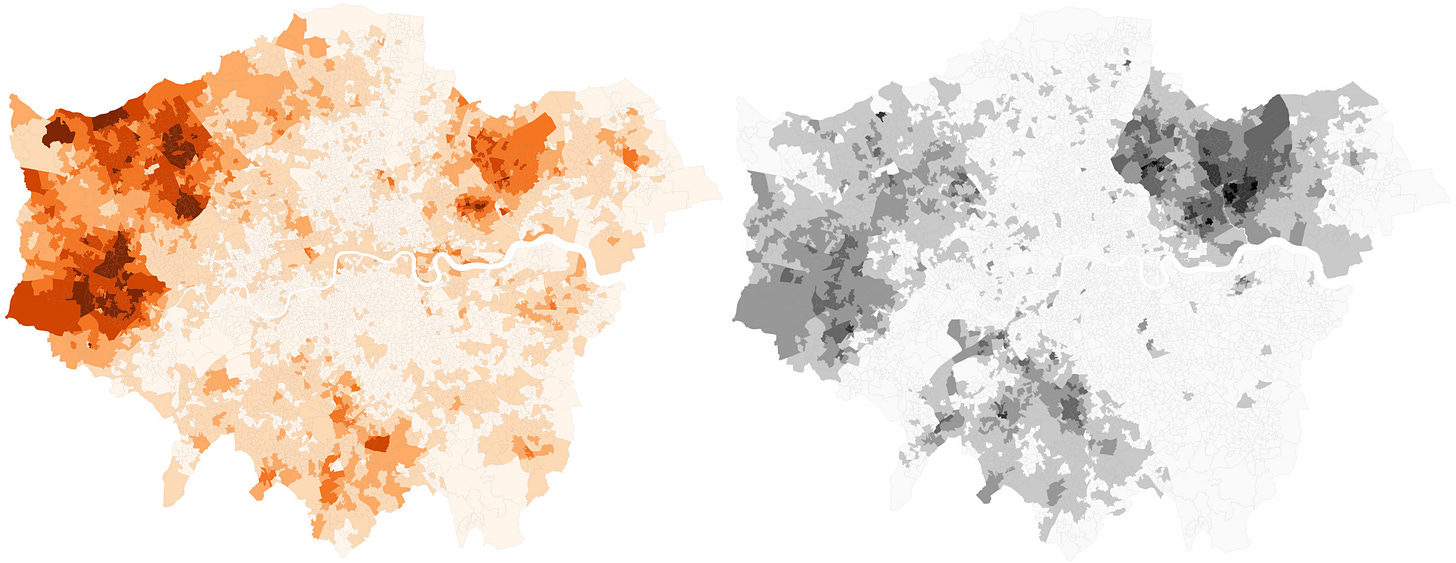

Often, these two communities live in relatively close proximity to one another, occupying different sections of Britain’s major urban areas. London, for example, is about 8 percent Indian (left) and 4 percent Pakistani (right), with both groups concentrated heavily in different areas of the city.

However, while both groups are concentrated unevenly in different parts of the capital, there are also areas of significant overlap; should conflict arise, we might expect these areas to serve as ‘flashpoints’. Ilford, for example, is about 17 percent Indian and about 14 percent Pakistani. It’s easy to see how an India-Pakistan War could provoke significant tensions in an area like this.

A similar story emerges when looking at the demographic profile of the West Midlands, Leicester, Blackburn, Preston, and a dozen other towns and cities. All of these areas have sizeable populations of both Indian and Pakistani extraction. In the event of a war between the two countries, it is easy to see how large areas of the country could devolve into low-level violence, persistent protests, and gridlock in local politics.

The idea that Britain is subject to this kind of disorder in response to a foreign conflict is not more speculation. Since Hamas’ attack on Israel, back in October 2023, the Israeli war in Gaza has spilled over onto our streets. The impacts of that conflict on British politics include, but are not limited to:

the breaking of the Labour Party’s traditional hold on the Muslim vote, and the emergence of independent candidates who presume to act on behalf of the Muslim community

persistent protests, demonstrations, and low-level civil disobedience in many of the UK’s largest cities, with as many as 300,000 attending the 11th November protest in London. Counter-protests, led by pro-Israel groups, have attracted smaller crowds

major, persistent protests at most of the UK’s major universities, alongside sustained student pressure to encourage universities to divest from investments in Israel

sit-ins at major train stations, including London King’s Cross, London Waterloo, Liverpool Lime Street, Manchester Piccadilly, Edinburgh Waverley, and Glasgow Central

direct action by trade unions (including blockades) at UK arms factories supplying arms to Israel

a disproportionate focus on the Israel-Palestine conflict in Parliament, given Britain’s limited influence and interests in the region

concerted attempts to intimidate politicians, both local and national, for their position on the conflict; disruption of local council meetings across the country

school strikes in Bristol; walk-outs from students in Luton

Let me be clear - the impact of the Israel-Palestine conflict on British politics has not been overwhelming. However, given Britain’s limited influence and interest in the conflict, it has played an outsized role in shaping political discourse, causing significant disruption to political and civic life. Most consequentially, it also served as the catalyst for the dissolution of the traditional alliance between Muslim voters and the Labour Party.

An India-Pakistan War would make Israel-Gaza look tame. There are millions of Indians and Pakistanis in this country, many of them with direct and enduring ties to their homelands. Given the weakness of the British state, protests and demonstrations could quickly devolve into rioting. Indeed, there are already recent examples of outright conflict between Indians and Pakistanis on British streets.

In August 2022, rioting broke out between Hindus and Muslims in Leicester, in the wake of an India-Pakistan cricket match. The fighting lasted for around a month, and resulted in twenty-five injured police officers, alongside forty-seven arrests. Both communities allege the involvement of extremist groups on the other side.

By the following month, the conflict spread had to Birmingham. On September 20th, video footage showed nearly 200 Muslim men surrounding the Durga Bhawan Temple in Smethwick, in protest at the attendance of Sadhvi Rithambara, a controversial Hindu nationalist speaker.

The events in Leicester paralysed the city for a month. They were prompted by a mixture of low-level tensions over the Kashmir issue, and heightened tensions over cricket. Despite this relatively weak pretext, these riots rendered an entire city ungovernable for a month. An out-and-out war between the two countries would be significantly more explosive and emotive.

Not all members of the Indian and Pakistani communities in the UK support the government of their homeland. A great many Indians are critical of Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist agenda; similarly, a great many Pakistanis deplore the government in Islamabad. However, an India-Pakistan War would likely harden nationalist sentiments amongst both communities. Even if these sentiments only took root amongst a vocal minority, these communities are now so large that this would nevertheless create significant disorder and political disruption.

At a fundamental level, an India-Pakistan War would be personal for thousands of people living in Britain today. Many South Asians in Britain still have family in the subcontinent - in 2021, 44 percent of UK Indians had been born in India, while 37 percent of UK Pakistanis had been born in Pakistan. Given the post-2021 uptick in migration from these two countries, that percentage has likely increased in recent years. It is therefore easy to imagine that many South Asians would aim to influence the British Government to adopt a particular position on the conflict - either through political lobbying, protests, riots, or the intimidation of political figures.

Every tactic employed by pro-Palestine campaigners since October 2021 would be employed by both the Indian and Pakistani camps in the UK; both camps would likely be larger than the pro-Palestine faction, and would have significantly closer links to the governments of their respective countries.

As I highlighted in my recent article on Indian migration to the Anglosphere, recent waves of migration from India have been accompanied by the rise of Hindu nationalist groups, many of which have explicit ties to the Indian Government. This includes, but is not limited to, the Hindu Forum of Britain (HFB), the Overseas Friends of the BJP, the Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh, the National Hindu Students’ Forum, and Vishwa Hindu Parishad UK. These groups are often linked to the Sangh Parivar, the Hindu nationalist umbrella organisation which includes India’s ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). BJP-linked groups have explicitly sought to influence British elections; Trupti Patel, President of HFB, put it best, when she told the Times of India, “let’s play the politics of bloc voting”.

These groups were also linked to the violence in Leicester, with a recent Home Office report acknowledging that “Hindu nationalist extremism” played a part in fomenting the riots. With this backdrop in mind, it is easy to imagine how Hindu nationalist groups could attempt to influence the British political establishment towards support for India, through both violent and non-violent means.

Meanwhile, an influential Pakistani lobby has also emerged in Britain, which includes figures associated with Tehreek-e-Labbaik, an Islamist political party known for its violent support for blasphemy laws. It is easy to imagine that the Pakistani cause would soon become intertwined with the broader ‘Muslim’ cause, a phenomenon which has already taken place as regards the Palestinian cause. In turn, this would likely prompt activity from prominent Muslim groups, such as the Muslim Council of Britain and the Muslim Public Affairs Committee UK, both of which have previously advocated for the Pakistani position on Kashmir.

All of a sudden, major political parties would be forced to choose between Indian voters, Pakistani voters, and the great majority of ordinary Britons, who would likely be frustrated by the degree of attention paid to this far-off conflict.

This political challenge would likely prove especially challenging for the Labour Party, which enjoys a strong base amongst both Indian and Pakistani voters. According to a YouGov poll conducted before the 2024 General Election, Labour was due to win 40 percent of the Indian vote, and 44 percent of the Pakistani vote - alienating either community by taking a firm position on the conflict could prove politically costly. Labour’s response to the Israel-Palestine conflict suggests that the party is more likely to pursue a ‘middle way’, rather than issuing an outright endorsement to either side.

In walking this tightrope between its Indian supporters and its Pakistani supporters, the Labour Party could end up adopting a compromise position which pleases nobody. Their prevarication could drive away Pakistani voters, who increasingly have independent alternatives - and could hasten the Party’s already-declining fortunes with Indian voters. In areas like Ilford, the sudden alienation of these two major communities could result in a fracturing of the traditional political system.

The Conservatives, meanwhile, have aligned themselves more closely with India in recent decades - but could face pressure from the right to distance themselves from the conflict altogether. While some neoconservatives have attempted to frame India as an essential part of the ‘democratic West’, their efforts in this case have been less successful than in the case of Israel - it’s difficult to imagine much enthusiasm for the Indian cause, even amongst figures on the intellectual right. Nevertheless, given the Conservative Party’s track record of overt appeals to Indian voters, it’s easy to imagine the party framing itself as a champion of the Indian cause, if only in hopes of winning the support of Indian voters.

In and of itself, the fact that Britain’s response to the conflict would be shaped entirely by domestic ethnic politics is a cause for concern. Our position on any given geopolitical crisis should be driven by our strategic, economic, and political interests - instead, thanks to decades of mass migration, British foreign policy is now subject to the whims of powerful ethnic lobby groups. Does this really serve the interests of ordinary Britons?

In the case of an India-Pakistan War, our inability to pursue a genuinely self-interested foreign policy would be particularly concerning. The Indian economy is now a significant global player, with a GDP totalling some $4.3 trillion; the Pakistani economy is smaller, at $338 billion, but still significant. A war between these two countries would have significant implications for global supply chains. India supplies around 20 percent of all generic drugs in the world, and around 33 percent of all generic drugs in the UK. These drugs account for around four out of every five NHS prescriptions. An India-Pakistan War would undoubtedly disrupt the production of these drugs, which could cripple the NHS overnight - but given the scale of ethnic lobbying and conflict, would the British Government really be able to navigate this sudden shock with the appropriate degree of pragmatism and self-interest?

Likewise, India is the world’s largest exporter of rice; Pakistan is the world’s fourth largest exporter. Large-scale disruption of production in both countries, and the redirection of exports for domestic consumption, would place significant pressure on global food supply chains. A majority of the UK’s rice is imported from either India or Pakistan. An India-Pakistan conflict would undoubtedly restrict our ability to import this staple good, driving up prices at a time when the cost-of-living is already a challenge for many ordinary Britons.

The list of economic challenges goes on and on. How would an India-Pakistan conflict impact the global IT industry - in turn impacting the UK’s critical services sector? Both countries are major exporters of textiles and garments - how would an India-Pakistan conflict shape the UK’s clothing supply chain? Could a conflict in South Asia disrupt the flow of Persian Gulf oil? In addressing each of these challenges, the UK Government would ideally be driven by pragmatism and self-interest - an ideal which will be rendered impossible by demographic reality.

Even thornier is the issue of population flows between Britain and the subcontinent. Under the Foreign Enlistment Act 1870, it is a crime for British citizens to serve in a foreign military which is at war with another foreign state. How would the UK Government react to the involvement of British citizens in either the Indian or Pakistani military? How might that reaction shape its relations with either of the two governments?

Perhaps most concerning is the potential that an India-Pakistan conflict has to create a refugee crisis. The two countries are amongst the densest in the world, and are some to a combined 1.68 billion people. A war between the two countries would undoubtedly displace millions; second-order disruptions to supply chains could disrupt hundreds of millions. Thanks to natural disasters and existing low-level conflict, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre estimates that the two countries are already home to some 1.9 million internally displaced people (IDPs). In the context of a war, this figure would increase rapidly - and is unlikely to remain internal.

Given the large footprint that the Indian and Pakistani communities already have in the UK, Britain would undoubtedly be one of the top destinations for South Asian refugees. Those with familial links here would likely seek to use these ties to justify their emigration. Likewise, in the political arena, expect to see special interest groups lobbying for bespoke refugee schemes for both nationalities. Given the British political establishment’s track record on immigration, do we really believe that they would wash their hands of the situation? Badly-handled, an India-Pakistan War could see Britain suddenly import millions of South Asians, in the midst of a war in that part of the world. Do we really believe that these new arrivals would leave their grievances at the door? More likely, these new arrivals would only exacerbate the ongoing conflict between Indians and Pakistanis based in the UK.

But maybe this is all idle speculation. Maybe the prospect of an India-Pakistan War is altogether unrealistic. I certainly hope so - but I fear not.

Since the two countries became independent in 1947, they have participated in six wars, the most recent of which concluded in 2003. Since the turn of the millennium, there have been ten major border skirmishes and military stand-offs between the two countries, the most recent of which took place in 2023. The India-Pakistan border is one of the most heavily militarised borders in the world. In January 2023, former US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo revealed that India and Pakistan “came close” to a nuclear war in February 2019, after India launched strikes against militants in Pakistan. In Never Give An Inch: Fighting For The America I Love, Pompeo said that he “does not think that the world properly knows just how close the India-Pakistan rivalry came to spilling over into a nuclear conflagration in February 2019.”

The ongoing insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir remains a significant point of tension for the two countries; India accuses Pakistan of supporting militant groups which have executed several terrorist attacks across India. As recently as April 2nd, Indian and Pakistani troops exchanged fire across the Kashmir frontier; four casualties were reported in February. Similarly, in Baluchistan, Pakistan has accused India of supporting insurgent groups; in 2016, Pakistani authorities arrested an Indian spy who was said to be supporting separatist groups in Baluchistan. With both countries facing significant pressure on water resources, Siwat Varnakomola at King’s College London has highlighted the Indus River as another potential source of conflict between India and Pakistan. While 90 percent of the Indus River’s water resources are allocated to Pakistani agriculture, India controls the river’s source, and has begun to build hydroelectric dams upriver, which could potentially threaten Pakistan’s access to much-needed freshwater.

But how real is the risk that these nascent tensions turn into a real war? In 2024, the Annual Threat Assessment Report, released by the US Directorate of National Intelligence, argued that “Pakistan’s long history of supporting anti-India militant groups and India’s increasing willingness, under the Modi government, to respond with military force to perceived or real provocations from Pakistan raise the risk of escalation during a crisis”. While the crises of recent years have been resolved peacefully, the situation remains febrile. Both the Indian and Pakistani governments are nationalist in character, and have repeatedly emphasised their right to take unilateral action in the pursuit of the national interest. Both countries also have assertive, influential militaries, which openly view the other country as a threat.

The truth is, nobody knows how likely an India-Pakistan conflict is. But with every passing year, there is a risk that low-level skirmishes at the border turn into full-blown war, as has happened six times since 1947. A confident, chauvinistic India, and an insecure, unstable Pakistan create the perfect conditions for a full-blown conflict between the two countries - with India keen to show its newfound strength, while Pakistan seeks to distract from domestic troubles by invoking the external enemy.

One thing is for sure - any such conflict between the two countries would be a disaster for Britain. As long as we continue our policy of mass migration from South Asia, we will be vulnerable to events there. In a worst-case scenario, an India-Pakistan War could cause riots on the streets, paralyse our politics, disrupt our economy, and push thousands of refugees into the UK, at a time when our country is already buckling under the weight of immigration.

It did not have to be this way; successive governments have chosen to import ethnic conflict from the rest of the world, to a country which was largely insulated from such problems - with the notable exception of Northern Ireland. We must, unfortunately, take this threat seriously. That means restricting the activities of groups which act on behalf of foreign states. Neither India nor Pakistan are our friends - we should act accordingly, and root out their influence networks in this country.

But most importantly, it also means heavily restricting immigration from South Asia. The risk that an India-Pakistan War poses for Britain is primarily the result of mass migration. If we do not want to leave ourselves vulnerable to conflict in far-flung corners of the world, we should make sure not to import millions of people from those conflict zones.

When Britain left India in 1947, the vast majority of ordinary Britons will have hoped that our withdrawal would absolve Britain from involvement in the sectarian conflict which has defined that region for centuries. It is a cruel twist of fate that we should now end up managing those conflicts on our own streets, some eighty years later.