Riding The Tiger: Why The Anglosphere Should Be Wary of India

A tale of Hindu nationalism and H-1Bs

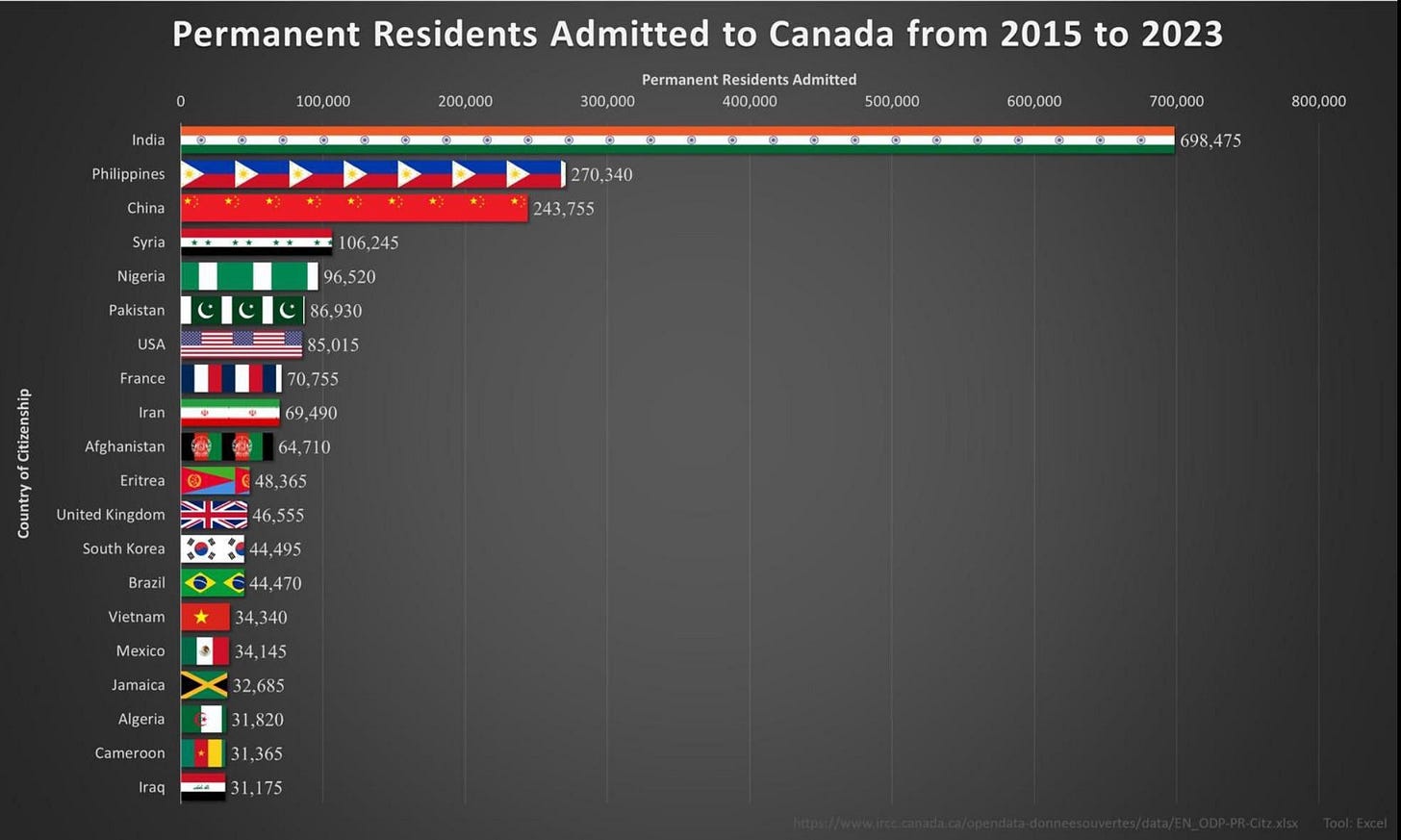

In the four years from 2021 to 2024, more than 1 million Indians immigrated to Britain. In Canada, Indian immigration has surged 326% over the past decade; south of the border, in the United States, Indians make up the second-largest foreign-born population, behind only Mexicans. In both Australia and New Zealand, Indians now comprise the single largest source of migration.

Really, it was only a matter of time before mass Indian migration landed on Anglophone shores. Over the past few decades, India’s population has exploded, with nearly 400 million people added to the country’s population since the millennium. At the same time, its economy has shaken off the constraints of the ‘License Raj’, with Indian GDP per capita rising sharply since the country’s 1991 balance of payments crisis. As a result, many millions of Indians are now wealthy enough to emigrate - as many as 450 million Indians are now considered ‘middle class’. While poor Indians rarely have the means to emigrate, and very rich Indians have little need to, this vast and growing middle class is hungry for economic opportunity overseas.

This impetus to emigrate will persist until India reaches a similar level of development to its Western counterparts - which, as of now, seems a distant dream. India’s most developed state, Goa, has a Human Development Index score (0.760) similar to Colombia (0.758) or Moldova (0.763). Nationwide, India (0.644) sits below countries like Iraq (0.673) and Bangladesh (0.670), with poorer states like Bihar (0.577) ranking alongside Zambia (0.569) and Cameroon (0.587). While wages remain low and infrastructure remains relatively poor, many Indians will remain drawn to emigration.

And the Indian Government has significant incentives to encourage emigration. In 2024, India was the world’s top recipient of international remittances, with $129 billion pouring into the country via the vast Indian diaspora. That’s a larger figure than many Indian states - the financial contributions of Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) plays a significant role in the country’s economic development strategy. In February of this year, Indian Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced plans to raise the threshold at which tax is collected on remittances, a policy which will further incentivise NRIs to send more of their money home.

This is particularly interesting in the light of India’s graduate underemployment crisis. As of March 2024, 29.1 percent of young Indians with university degrees were unemployed. Underemployment is also a problem; the acceleration of university education in India has not been matched by a commensurate increase in the number of graduate jobs. As such, many of these degree-holding Indians will undoubtedly look for prospects abroad. The Indian Government is therefore incentivised to push foreign states to take India’s unemployed graduates who will, in turn, support the Indian economy through remittances.

This often takes place under the auspices of ‘skilled’ migration. It is worth noting that holding a university degree does not necessarily make an emigrant “skilled” - according to the Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2025, just a single Indian university (the Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru) ranks in the top 500 global universities. While some Indian emigrants are doubtless capable and talented, we should be deeply sceptical about the idea that Indian degree holders are automatically ‘skilled’, given the relatively poor standard of Indian higher education.

And where are these Indian migrants going?

In general, recent Indian emigrants have been drawn to two country groupings. The first are the Arab monarchies of the Persian Gulf - the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Oman, Kuwait, and Bahrain. These countries are almost entirely reliant upon immigrant workers, with little native participation in the labour force - a result of their vast oil wealth. Small, rich Arab populations have met the labour demands of their rapidly growing economies with migrant labour - albeit under the kafala sponsorship system, which deliberately bars foreigners from attaining political or cultural power.

The second group are the Anglophone nations - the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Thanks to the historical legacy of the British Empire in the Indian subcontinent, as many as 230 million Indians speak English. It is therefore unsurprising that many Indian immigrants would seek passage to the Anglophone world; if nothing else, the linguistic link is likely to smoothen the process of face-value integration.

Combine these demographic factors with loosened border controls - courtesy of Biden, Johnson, and Trudeau et al. -, and it’s easy to see how the Anglosphere’s Indian migration wave began. More than 10 million Indians now live across these five countries - a figure which is growing rapidly.

And yet, even as Anglophone conservatives have begun to take aim at migration waves from Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East, criticism of Indian immigration remains controversial.

For many Anglophone conservatives, immigration from India is an uncomplicated good. According to popular cultural perceptions, Indian immigrants are hard-working and family-oriented. They often display traditional markers of successful integration - high wages, high educational attainment, and low propensity to commit violent crime. There is a quiet hope in some quarters that Indian immigration will provide a right-leaning electoral counterweight to immigration from other parts of the Third World. If the political left can rely on the votes of particular immigrant communities, why shouldn’t conservatives rely on the votes of hard-working, family-oriented Indians?

For geopolitical hawks, India provides a ready-made bulwark against China, an Asian beachhead against the West’s adversary in a new Cold War. Western critics of Islam see a fellow traveller in the Hindu populism of Narendra Modi, who has been accused of condoning violence against Muslims during his tenure as Chief Minister of Gujarat. According to the ‘us and them’, ‘West versus rest’ worldview of some right-leaning commentators, India stands as a vital outpost of democratic civilization in the war against oriental despotism.

My contention is that both of these narratives are inaccurate and self-destructive. The first narrative overstates the ‘economic success story’ of Indian migration to the Anglosphere, and understates significant negative externalities in the cultural/political sphere. In particular, Indian immigration has given rise to sectarian political advocacy which hampers the ability of Anglophone states to behave in their geopolitical self-interest; it has also embedded a culture of fraud and nepotism in many institutions, both public and private.

The cultural similarities between Western conservatives and the median Indian immigrant are also vastly overstated; there is little evidence that Indian immigrants provide a reliably right-leaning electoral constituency. In order to continuously win Indian support, parties of the political right will need to pander to particular cultural and geopolitical hobbyhorses, often to the detriment of their principles and the national interest.

The second narrative is naïve in the extreme, and fails to recognise the fact that India is both mercurial and self-interested. India cannot be relied upon as a partner. The Indian Government is ruthlessly self-interested, and is willing to form alliances of convenience with whomever will benefit India. The Indian Government has been aggressive in its dealings with Anglophone nations before, and has actively weaponised its diaspora as a diplomatic tool. A significant segment of the Indian ruling class harbours post-colonial resentment towards Britain - but this resentment often spills over into sentiments towards other Anglophone nations. None of these facts are, in and of themselves, a barrier to productive relations with India - this is simply how self-interested states behave. However, they should highlight the folly of dewy-eyed Western narratives about India as an outpost of freedom and democracy in Asia.

It may seem strange to tackle both migration and geopolitics in the same article. These are both major topics, each multifaceted and complex - why combine the two? In the case of India, these two issues are inextricably linked; migration is both a tool of and an aid to Indian foreign policy. Modi’s India explicitly seeks to use its diaspora - termed ‘living bridges’ - to exercise influence abroad. Speaking in 2015, BJP General Secretary Ram Madhav explicitly argued that the Indian diaspora “can be India’s voice…that is the long-term goal of diaspora diplomacy”. At the same time, the Indian Government has been assertive in pushing for easier migration for Indians - even arguing that Indian migrant workers should be exempt from National Insurance payments in the UK.

In tandem, these two factors create a self-reinforcing loop - the Indian Government pushes for more relaxed immigration rules for Indians, who then support the Indian Government’s geopolitical objectives from their host country. This makes it easier for the Indian Government to advocate for a relaxation of immigration rules - and thus the cycle continues.

I do not intend to overstate my case. In general, it is true that Indian migration has been more positive for the Anglosphere than migration from other regions of the world, such as Sub-Saharan Africa. In general, it is true that Anglophone nations should not treat India with outright hostility. Even under a more restrictive immigration system, it is true that some Indians would provide a genuinely valuable contribution to strategic industries in the Anglosphere nations.

That said, my core argument is as follows:

(1) The degree of achievement and integration demonstrated by Indian immigrants in the Anglosphere is generally overstated.

(2) The median Indian immigrant is by no means “top talent”, and even skilled Indian migration has been susceptible to a relatively high degree of nepotism and fraud.

(3) There are also a number of negative political/social externalities associated with recent waves of migration from India, which are rarely acknowledged by advocates of increased Indian migration.

(4) Narendra Modi’s India is a not a ready-made geopolitical ally, and Indian culture is more distinct from mainstream Anglophone culture than is often recognised.

(5) As such, Anglosphere nations should be far more cautious about their embrace of India, both in geopolitical terms and in regards to migration.

The interface between the Anglosphere and insurgent India will be one of the defining stories of the 21st century. For the United States, an incautious approach to India will leave the country with a poorly-calibrated migration system and a weakened geopolitical position in Asia. Failure to address the shortfalls of the current H-1B visa route, which has effectively turned into a channel for India’s surplus graduate population, could see the American tech sector hampered by nepotism and anti-competitive practices.

For the smaller Anglosphere nations, navigating the challenge of India is even more important; indeed, it is of existential importance. According to the latest figures from the Office for National Statistics, Britain admitted 240,000 Indians to the country in 2024. Even assuming a reduced rate of 200,000 Indians a year, the UK could be set to import another 2 million Indians over the next decade. That’s on top of the 1 million Indians who came to the country between 2021 and 2024, and the 1.92 million Indians residing in the UK as of the 2021/22 census. Change at this pace is unsustainable, undesirable, and potentially irreversible - and will bring little economic benefit. As I will demonstrate later in this article, new cohorts of Indian migration have already diminished the (overstated) contributions of previous cohorts. Britain’s new Indian population will not prove to be reliably conservative - and could prove problematic in our attempts to stand up for our national interests against an increasingly assertive India.

After years of sleepwalking and sentimentality, the nations of the Anglosphere must now recalibrate their approach to India. Whole-hearted embrace must give way to caution and scepticism; we cannot afford to absorb the surplus population of a chauvinistic rising power.

The rise of India: repeating the folly

India’s rise to global prominence has undoubtedly been one of the more interesting stories of the early 21st century. Since the liberalisation of the Indian economy in 1991, the country has begun to emerge as a serious economic player, after decades of underperformance, overregulation, and poverty.

At the turn of the millennium, India’s economy was the 13th largest in the world, behind countries like Spain and Brazil. Today it stands in 5th - and is soon projected to overtake sluggish Germany and Japan, leaving India as the world’s 3rd largest economy by 2030. In 2025, the Indian economy is expected to grow at between 6.4 percent and 6.6 percent; Indian firms now compete with their Western and Chinese counterparts for lucrative public sector contracts across the world. In April 2023, India overtook China to become the world’s most populous country.

These economic and demographic strides have been accompanied by a more assertive diplomatic, cultural, and military position. This has been particularly true under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi (2014 - ) and External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar (2019 - ). Jaishankar has urged the West to “mind its own business” over India’s close ties to Russia, and has accused countries such as Canada of “cherry picking” in their commitment to principles such as territorial sovereignty and non-interference. International commentators have begun to refer to India as the “voice of the global south”, while the country’s 2023 G20 Presidency showcased Delhi’s growing power.

On an individual level, rising India has also been marked by the success of the Indian middle class, both at home and in diaspora. With Sunder Pichai leading Google, Satya Nadella leading Microsoft, and Ajay Banga serving as President of the World Bank, Indians now occupy some of the most prominent positions in global business. In the political arena, figures such as UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and US Vice-President Kamala Harris exemplify the political success of diaspora Indians. These individual cases have contributed to extant Anglophone cultural narratives about Indians - hard-working, mercantile, successful.

Combined with relatively high average wages and relatively low crime rates, it’s easy to see why many Anglophone conservatives view Indian migration as a success story.

There are also a number of less tangible reasons for this. Thanks to the legacy of the British Empire in the subcontinent, educated Indians often share cultural reference points with their Anglophone counterparts. As noted previously, millions of Indians are proficient in the English language and enjoy English-origin sports such as cricket; meanwhile, Indian food and Indian film has found increasing popularity in the Anglophone world. Indians are perceived as family-oriented and religiously moderate, like the Anglophone middle class. For a certain type of Anglophone rightist, Indians provide a useful narrative crutch when arguing that mass migration can be successful, a favourable alternative to migrants from the Middle East and Africa.

However, these superficial similarities obscure a number of important differences.

The first is on the subject of “family values” - an ever-nebulous and unhelpful term. “Family values” are not a fixed constant; they differ considerably from society-to-society.

The family systems model of French anthropologist Emmanuel Todd demonstrates this point. According to Todd, the Anglosphere is nearly unique in its adherence to an “absolute nuclear” family structure - such a model is traditionally shared by some north-western European nations such as the Dutch and the Danes, but by few other cultures worldwide. Under the “absolute nuclear” family structure, kinship ties are loose and broadly voluntary. According to historians Alan Macfarlane and Peter Laslett, this has been the primary mode of family arrangement in England since at least the 13th century - two parents, with their children, living in their own property, with relatively few obligations to their extended kin. Our “family values” have generally meant monogenerational households and individuated responsibility.

This unique family structure, alongside the near-absence of consanguineous marriage, birthed many of the other anthropological features of the Anglosphere. For one, it enabled a high degree of economic mobility - or ‘neolocality’, the anthropological practice of new families settling away from the parents of either husband or wife.

Without ties to extended kin, families were free to migrate in search of economic opportunity - first internally, and then to the colonies. English commoners were far less rooted to the land than their continental counterparts. In the words of sociologist Brigitte Berger, “the young nuclear family had to be flexible and mobile as it searched for opportunity and property. Forced to rely on their own ingenuity, its members also needed to plan for the future and develop bourgeois habits of work and saving.”

In novel contexts, whether the streets of London or the logging settlements of Upper Canada, migratory Anglophone families needed to work alongside unfamiliar people. This, in turn, necessitated a culture of reliance on strangers, rather than on family members. In response to this pressure, social and political norms emerged which prized individuated responsibility, while enabling strangers to trust one another - high-trust, and high-honesty.

Loose kinship networks and the need to rely on strangers also laid the foundations for meritocratic forms of selection, which promote ability over existing allegiances. After all, if blood ties cannot be relied upon, then people must find other metrics by which to determine trustworthiness, capability, and suitability for promotion.

Put simply, the core societal unit of the Anglophone world is the individual, not the clan. Our societies are designed to function on the basis of individuated meritocracy, rather than on the basis of nepotistic kinship networks. Individuals are judged on capability, and suitability, and are expected to trust, hire, and work alongside strangers. Their relations with others, including with family members, are conducted on a voluntary basis. This creates a society in which the most talented can rise to the top, and which prizes individualism over conformity.

However, given that meritocratic societies depend upon a high degree of social trust, they are vulnerable to disruption from low-trust, high-nepotism groups. Such groups are able to take advantage of high-trust social institutions - fraud and nepotism often go unremarked upon, and are presumed to be the result of genuine meritocracy. As such, when admitting outsiders, societies with nuclear family structures should be discerning - not just in regards to economic potential, but in regards to social trust and commitment to meritocracy.

In India, Todd identifies a number of different family structures. In northern India, he identifies an exogamous, patrilineal, and communitarian (EPC) family structure. Under communitarian family systems, individuals owe a relatively high degree of obligation to their kin - there is an expectation of mutual support, care, and obligation. In such cultures, nepotism is common - society can be seen as a zero-sum competition, with different families competing over resources and status.

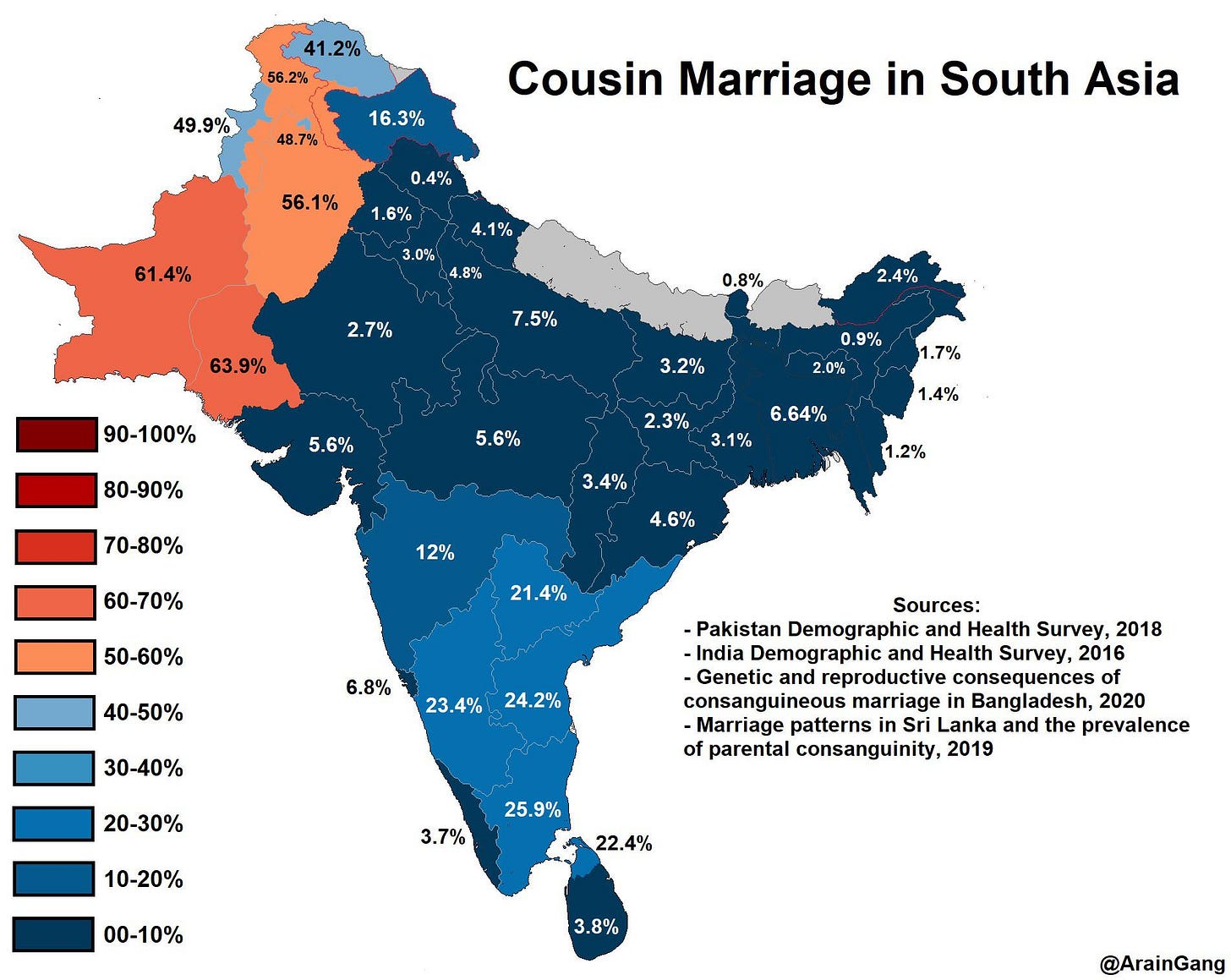

In exogamous cultures, marriage tends to happen outside of the family, with a relatively low degree of consanguineous marriage - this fact is reflected in the relatively low rate of cousin marriage in northern India. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the rate of cousin marriage in northern Indian states (as high as 7.5% in Uttar Pradesh, population: 240 million) is still significantly higher than in Anglophone nations.

In patrilineal cultures, brothers are considered equivalent (i.e. relatively little preferencing of older siblings), but sons are generally elevated above daughters. According to 2022 research by Pew, just 42 percent of Indians say that sex-selective abortions are completely unacceptable.

Management of families in EPC family cultures tends to fall to older relatives, and intergenerational living is common; it is no coincidence that such cultures tend to produce the “tiger mom” stereotype of pop culture fame.

Amongst the primarily Dravidian populations of southern India, Todd identifies a greater tendency towards nuclear families - but with caveats. Here, patrilocality is common (i.e. it is common for new families to live with the husband’s parents), and within-clan marriage is also significantly more common than in the Indo-Aryan north.

In comparison to the absolute nuclear social structure of Anglophone societies, both of these models are unusually clannish, communitarian, and collectivist. They are also less prone to promoting social trust and meritocracy; in modern India, this is reflected in numerous measures of social trust and impersonal honesty.

The Corruption Perceptions Index, published annually by Transparency International, measures experience of public sector corruption. All five Anglosphere nations perform well, landing in the top 25 countries - with New Zealand in 3rd. India, by contrast, ranks 93rd. TI’s Global Corruption Barometer Asia also found that India has the highest bribery rate in Asia (39%) and the highest number of people who use personal connections to access public services (46%). Stripe’s country-by-country fraud radar identifies a higher rate of fraud in India than in any other country. Fraud, corruption, and low-trust behaviour are endemic in Indian society. We should not expect these behaviours to disappear upon immigration to the West; they are not merely a response to systemic stimuli, but an ingrained cultural attitude. In low-trust societies, where families are seen to be competing over a limited pool of resources, these behaviours are regarded as an acceptable way to ‘get ahead’. Loyalty is first owed to the family, and then to caste, or religion, or ethnic group.

Unfortunately, this fraud also extends into the professional sphere. A 2019 analysis of retractions in biomedical science journals found that more than half of retractions from India were the result of duplication or plagiarism. In the United States and the United Kingdom, most retractions were the results of error, or authorship disputes. While retractions from major publications have increased across the board, the rise in retractions of Indian research - 125 percent between 2017 and 2022 - greatly outstrips the global median - 25 percent over the same period. In zero-sum cultures, “getting ahead” is a more important virtue than impersonal honesty.

This zero-sum attitude is also reflected in attitudes to wealth. 2022 research, produced at Stanford University and published in PNAS, assessed global perspectives on the ‘selfish rich inequality hypothesis’ - the idea that the rich are rich because they are selfish. In that study, no single country believed in this idea more than India - while Anglosphere countries clustered towards scepticism of this idea. Canada, the United States, and Australia were the three countries with the most positive views about sources of wealth inequality, while the United Kingdom had a significantly more positive view than the mean.

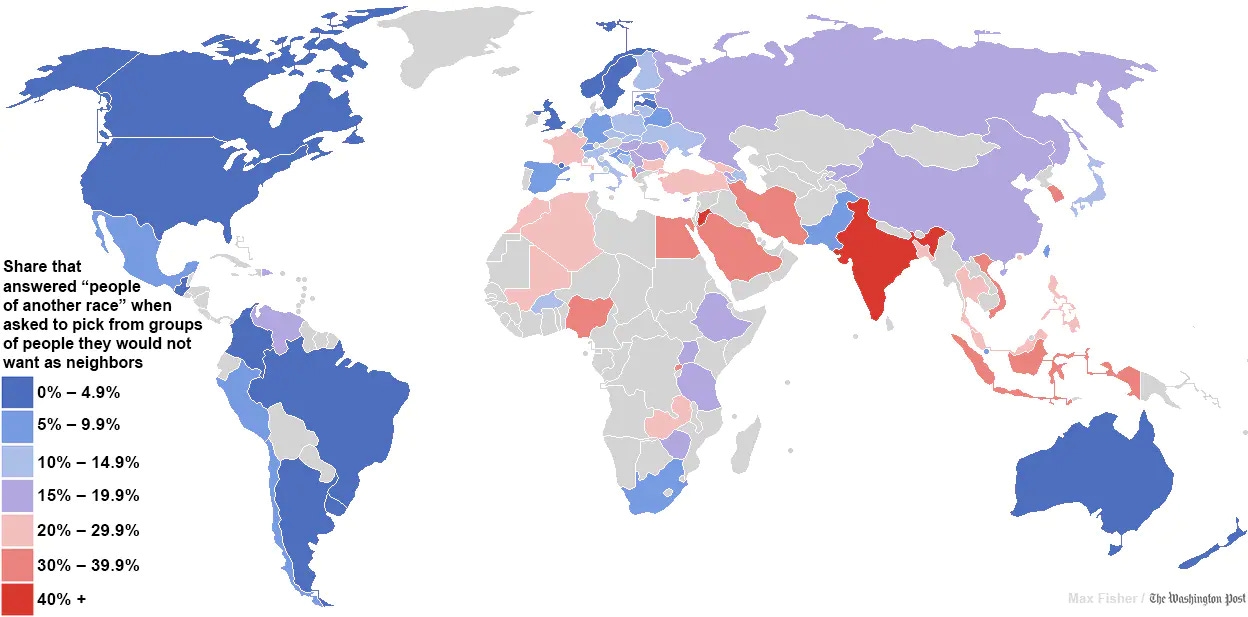

This zero-sum attitude also extends to attitudes towards race. In 2013, the World Values Survey asked respondents from eighty countries to identify groups of people who they would not want as neighbours. Anglosphere nations were uniformly the most tolerant and pluralistic on this metric - while a full 43.5 percent of Indians said that they would not want a neighbour of a different race. Once again, we should not expect this attitude to disappear when Indians reach the West - it is a culturally-ingrained response to competition between different groups (familial, cultural, racial, and religious).

And a brief note on innovation, given the recent debate over H-1B visas (more on this below). Of the 133 countries ranked by the WIPO Global Innovation Index (an annual measure of per capita), India sits just 39th, behind countries like Bulgaria and Turkey. This is not simply a feature of India’s sheer population size - China ranks 11th. For posterity, the United States ranks 3rd, the United Kingdom ranks 5th, Canada ranks 14th, Australia ranks 23rd, and New Zealand ranks 25th. The most innovative nations are overwhelmingly in northern Europe, the Anglosphere, and northeast Asia.

In short, the presumed cultural similarities between the Anglophone middle class and the Indian middle class are largely superficial. In reality, Anglophone culture and Indian culture are not easily compatible. The former prizes small families, individualism, wealth creation, and social trust. The latter tends towards zero-sum thinking and communitarianism, with a latent tendency towards nepotism. Only at a fleeting, superficial level do the two share common values - and in fact, the norms of the former stand to significantly undermine the meritocratic norms of the latter.

But might we expect these norms to disappear, as Indian migrants interface with their Western counterparts? As the American economist Garett Jones argues in his seminal work, The Culture Transplant, “immigration, to a large degree, creates a culture transplant, making the places that migrants go a lot like the places they left. And for good and for ill, those culture transplants shape a nation’s future prosperity.” Analysing a wide variety of historical examples, Jones identifies one common trend - rather than conforming to the culture in which they find themselves, immigrants actually tend to make their host country more like the home country.

Given the preponderance of fraud, nepotism, and low-trust behaviour in Indian society, should we really welcome a ‘culture transplant’ from India? These traits are particularly dangerous for Anglophone societies, which place outsized importance on the value of social trust, meritocracy, and impersonal honesty.

Anglophone misapprehension about India is even more blatant at the geopolitical level. Narendra Modi is no ready friend of the West - he and his government are ruthlessly self-interested. While Western nations have closed ranks against Russia, following its February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, India has profited, acting as a middleman for the sale of sanctioned Russian oil onto international markets.

And despite the border tensions between Delhi and Beijing, the two countries have deepened their cooperation in recent years; bilateral China-India trade crossed $100 billion in the 2023-24 financial year. India is an enthusiastic participant in the BRICS club of nations - this year, Prime Minister Modi eschewed the biennial Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Samoa, instead attending the BRICS summit in Moscow. Western commentators should not fool themselves into believing that India is a ready-made ally, simply because it is a democracy with a history of battling Islamist extremism. Modi’s insurgent India is ruthlessly self-interested, its foreign policy characterised by a desire to deepen ties with a wide variety of partners. Strategic independence and influence projection are the name of the game.

In and of itself, a pragmatic and multipolar India would pose no inherent risk to the Anglosphere. However, this geopolitical positioning must be understood in the context of India’s ruling ideology. Since 2014, Indian has been ruled by Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The BJP is usually described as ‘right-wing’ by international commentators, and sometimes as ‘nationalist’ - but this obscures the fact that Modi and the BJP are motivated by a specific belief system - ‘Hindutva’.

First formulated in 1922 by V.D. Savarkar, ‘Hindutva’ is an ethnocentric ideology, inspired directly by European fascism. Savarkar’s ‘Essentials of Hindutva’ outlines his vision of a “Hindu Rashtra” (Hindu Nation) and an “Akhand Bharat” (Undivided India), stretching across the entire Indian subcontinent. According to Savarkar and his disciples, the core of Indian identity is Hindu identity. It is, in effect, Hinducentrism, which seeks to place Hindu identity at the core of Indian nationhood; it explicitly rejects the Anglo-inspired liberal pluralism of Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel.

The Hindutva worldview relies on a simple narrative - that India was once great, but that it was subverted by lesser civilisations who resented the exceptional qualities of the Hindu. Today, insurgent India’s success is resented by a shady coalition of socialists, Muslims, and Western imperialists. Hindutva paints Hindus as both victims and victors, locked in an existential fight for survival against domestic and foreign opponents. Indian successes are the product of the nation’s inherent cultural strength; Indian failures are the result of foreign interlopers.

Writers such as M.S. Golwalkar, a leading organiser of the modern Hindutva movement, have since expanded on Savarkar’s worldview. In ‘We or Our Nationhood Defined’ (published in 1939), Golwakar radically rejects the idea of a multi-ethnic India, suggesting that “the foreign races of Hindustan must either adopt the Hindu culture and language, must learn to respect and hold in reverence Hindu religion, must entertain no ideas but those of glorification of the Hindu race and culture […] or may stay in the country, wholly subordinated to the Hindu nation, claiming nothing, deserving no privileges, far less any preferential treatment - not even citizen’s rights.”

Hindutva’s ideological parallels with European fascism are not entirely coincidental. Savarkar was an admirer of Adolf Hitler and the German NSDAP. In a speech in August 1938, Savarkar endorsed National Socialism, and condemned Jawaharlal Nehru for his condemnation of Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy. In October 1939, he suggested that Germany’s policy towards the Jews be adopted by Indian Hindus against Indian Muslims; he deemed that “Germans and the Jews could not be regarded as a nation”. In March 1940, Savarkar celebrated Germany’s “revival of Aryan culture”, their glorification of the swastika, and their “crusade” against the enemies of Aryanism. In the aftermath of the Second World War, when details of the Holocaust had become widely known across the world, Savarkar was unrepentant in his support for Hitler - as late as 1961, he spoke favourably of German Nazism as an alternative to India’s “cowardly democracy”.

Despite his overt links to Nazism, Savarkar’s ideas found popularity amongst certain segments of Indian society. In 1925, K.B. Hedgewar, a disciple of Savarkar, founded the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (National Volunteer Union), or RSS. Over the following decades, the RSS would emerge as the leading advocacy organisation for Savarkar’s Hindutva movement.

The RSS was initially founded to instil “Hindu discipline” into India’s population, spreading the principles of Hindutva to “strengthen” India’s Hindu community. The RSS is both a volunteer organisation and a paramilitary group; its activities permeate every aspect of Indian society.

It also has significant links to Hindu nationalist extremism. When Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in January 1948, his killer - Nathuram Godse - was an active member of the RSS. In November 2003, two bombs planted by RSS members killed one person and injured thirty-four others at a mosque in Maharashtra. In 2007, a bomb placed by RSS members on a train travelling between India and Pakistan killed seventy people and injured a further fifty. In 2008, a bomb planted by RSS terrorists in Malegaon, Maharashtra, killed six and injured a further one-hundred-and-one. In the same year, the RSS and associated groups led rioting against Muslims and Christians in Odisha.

In September 2022, former RSS activist Yashwant Shinde revealed that he had been trained to carry out covert operations in Pakistan, and had actively planned to engineer a false-flag terrorist attack in India which could be used to scapegoat Muslims. Shinde suggested that key members of the RSS and the broader Hindutva movement were involved in the planning of these attacks, including the national secretary of Narendra Modi’s BJP.

Clearly then, Hindutva is a violent, Hindu supremacist ideology - but what does this have to do with Narendra Modi, and his BJP?

As part of its efforts to advance the Hindutva ideology, the RSS has been involved in cultivating a range of supportive civil society groups - dubbed the ‘Sangh Parivar’, or ‘Family of the RSS’. Member organisations of the Sangh Parivar include:

Vishva Hindu Parishad (World Council of Hindus), a Hindu religious organisation which has been involved in the demolition of mosques across India (including the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992), has supported the demolition of churches across India, and has been linked to the 2002 religious riots in Gujarat. On 4th June 2018, the VHP was classified as a militant religious organisation by the CIA.

Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), an Indian student organisation which has been involved in violent incidents on campuses across India. Most notably, in January 2020, masked ABVP members attacked members of the Jawaharlal Nehru University Students Union in New Delhi, smashing cars and pelting stones.

Bajrang Dal, a militant organisation, which was briefly banned by the Indian Government in 1992. Bajrang Dal has been involved in attacks on Christians; in 1998, it burned down dozens of churches and prayer halls in south-eastern Gujarat. In 2006, two Bajrang Dal activists were killed in Nanded in the process of bomb-making. On several occasions, the Bajrang Dal has acted as a “morality police”, harassing un-married couples on Valentine’s Day and invading gift shops selling Valentine’s Day merchandise.

The Sangh Parvar also includes the Bharatiya Janata Party - India’s ruling political party. While the BJP’s relationship with the Sangh Parivar has been complicated over the past few decades, the party remains reliant on the RSS and its satellites. Narendra Modi became a full-time worker for the RSS in 1971; he was assigned to the BJP in 1985.

As recently as February 2025, Indian press organisations have reported on the central role that the RSS has played in helping the BJP to win elections - most prominently in Delhi. Modi meets regularly with RSS leadership, and many of his senior colleagues are officially or unofficially associated with the Sangh Parivar.

So why do so many Western neoconservatives see Modi’s India as a natural ally?

Often, it is Muslims who are framed as the primary ideological enemy of Hindu nationalists. For much of its history, the majority of India fell under Muslim rule - whether by the Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526) or the Mughal Empire (1526-1857). Muslim rulers are responsible for constructing many of India’s most iconic landmarks, including Delhi’s Jama Masjid and Agra’s Taj Mahal. For Hindu nationalists, these centuries of Muslim rule represent a great humiliation, while India’s Muslim population (which numbers some 200 million) enjoy special privileges at the expense of the tolerant Hindu majority. So strong is this anti-Muslim sentiment that BJP legislators have called for the active destruction of the Taj Mahal.

Perhaps the most prominent recent example of the BJP’s anti-Muslim campaign is the party’s ongoing support for the reconstruction and refurbishment of the Ram Mandir, a Hindu temple built on the site of the now-destroyed Babri Masjid.

This can lead Western critics of Islam to view Hindu nationalists as natural bedfellows. Online Hindu nationalist accounts often draw directly on the work of British anti-Islam activists such as Tommy Robinson. Combined with India’s frosty position towards China, India can seem - at first blush - to be a natural conduit for Western interests in the Asia-Pacific.

But the West can just as quickly find itself the target of Hindutva ire. Foreign Minister Jaishankar has talked of liberating India from its “colonial mindset”, by “rejuvenating a society pillaged by centuries of foreign attacks and colonialism”. He has also been known to propagate false narratives about how the British “looted $45 trillion” from India - while smearing critics as “Hinduphobic”.

Since taking office in 2014, Modi has set about dismantling the remaining legacies of British presence in the subcontinent. He has repeatedly taken steps towards replacing the old system of British ‘personal law’, with a new uniform civil code which will erase communal arbitration mechanisms for non-Hindus. In May 2023, the country opened a new legislative building, replacing the Old Parliament House built by Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker in the 1920s. In 2019, a new National War Memorial was inaugurated in Delhi; nearby India Gate, which commemorates the British Indian servicemen who died in both World Wars, has been quietly deemphasised.

In 2022, it was announced that a marble statue of King Edward V would be replaced with a statue of Subhas Chandra Bose, an Indian nationalist activist who collaborated with Nazi Germany during the Second World War. Bose is a widely-celebrated figure in India - indeed, I caught flak in January for a post which criticised Narendra Modi’s enthusiastic veneration of Bose.

Modi has also deemphasised the role of English as a shared language for all Indians, instead promoting Hindi as a common tongue for administration and business - a move which has been met with fierce resistance in the country’s linguistically diverse south. The two legislative seats reserved for the mixed-race Anglo-Indian community were abolished in 2020. Iconic Victoria Terminus, built in British Bombay, is now Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, Mumbai.

Often, the BJP’s Hindu supremacist ideology manifests itself in outright historical revisionism. Last month, BJP Governor of Rajasthan (pop. 68 million), Haribhau Bagde, perpetuated the Hindu nationalist conspiracy theory that the world’s first airplane was invented by an Indian. In any other context, this kind of bizarre anti-historical revisionism would be roundly condemned by Western conservatives. The prominence of such views is perhaps best highlighted by the ‘saffronisation’ of the Indian curriculum. Successive BJP governments, at both the state-level and at the federal-level, have sought to reform India’s curriculum to glorify figures such as V.D. Savarkar and Nathuram Godse (Gandhi’s assassin), promote ‘Vedic science’ and ‘Vedic maths’ as an alternative to Western orthodoxy, and erase both Muslim and colonial history from textbooks.

The list goes on and on. India’s ‘Saffronisation’ is well underway, and shows no signs of slowing. These decisions are the prerogative of the Indian Government - but Anglophone conservatives should not kid themselves into believing that this is a friendly ideology.

Anti-Western sentiment - and specifically anti-Anglo sentiment - is not an incidental feature of Hindutva; it is a core tenet. The Anglo, like the Muslim, is a living symbol of Hindu India’s subjugation; the ultimate desire of the Hindu nationalist is to correct this historical aberration, by surpassing and subjugating the former conqueror. We would be unwise to expect good-faith allyship from New Delhi; at best, we might be able to manage a cordially productive relationship. This is particularly true in light of the widespread violence which has characterised the Hindutva movement for the past century.

And lest you imagine that Hindutva is simply the ideology of isolated rural voters - Modi’s support doesn’t come from the sort of “left-behind” communities who support populist candidates in the Western world. According to 2017 research by Pew, 66 percent of Indians with no more than a primary-school education said that they had a “very favourable” view of Modi, rising to 80 percent among Indians with at least some higher education. Following the 2019 general election, a Lokniti survey found that 42 percent of degree-holding Indians backed Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), while just 35 percent of those with only a primary-school education did. Many of the Indians being enthusiastically imported by Anglophone nations agree with Modi’s agenda and ideology.

Yet despite all of this, many Anglophone conservatives continue to espouse the belief that closer ties with - and more immigration from - India will help to ensure lasting closeness between the English-speaking world and this rising power.

The Anglophone world has made this mistake before. In the late 20th century, many rightists sincerely believed that China would soon come into the Western fold, its society democratising alongside its liberalising economy. Speaking in Beijing, in 1996, Margaret Thatcher predicted that China would soon democratise - “open, stable, and prosperous, and a full partner in the international community”. It was under this misapprehension that Thatcher gladly agreed the timeline for the handover of Hong Kong, in 1984. In that speech, the Iron Lady even implied that she foresaw the process of Chinese democratisation taking place in the early 21st century - “I would only observe that it took countries like South Korea and Taiwan at least 20 years of economic progress from the levels at which China finds itself now, before they had more open and democratic political systems. This may seem a long time, but in the scale of China’s history, it is the blink of an eye.”

In Western policy circles, Thatcher’s view dominated until the mid-2010s - more engagement, particular in the economic arena, was supposed to lead to an inevitable process of middle class democratisation in China. In September 2014, the Harper government in Canada ratified a new Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement (FIPA) with China. In 2015, David Cameron infamously welcomed Xi Jinping to the United Kingdom for a five-day state visit. Even as Barack Obama oversaw an American strategic “pivot to Asia”, the former President enjoyed cordial relations with the Chinese premier.

It is only in recent years that the extent of this folly has become apparent to the political establishment. The West made assumptions about China which proved to be untrue in a fit of post-Cold War optimism. As a result, it left itself exposed to Chinese diplomatic, economic, and security objectives.

Failing to calibrate our assumptions about China has proven to be a costly mistake; failing to calibrate our assumptions about India could prove even more damaging. Unlike China, India’s economic system is not inherently limited by the excesses of state control. India is a democracy, but its ruling party and associated apparatus has shown itself more than willing to apply significant pressure to the Indian private sector and civil society. Unlike China, India’s population is not levelling off - based on current fertility trends, the country’s population is set to peak in the early 2060s. Unlike China, India has shown little willingness to stop its citizens from leaving the country - in fact, it has encouraged embraced as a geopolitical tool. While rising China has been able to leverage its economic influence to cause trouble for Western leaders, insurgent India may soon be able to perform the same trick - a tool made even more powerful by the presence of millions of diaspora Indians in Anglophone nations.

The canary in the coal mine: Indian immigration to Canada

Thanks largely to Canada’s relationship with the British Empire, a small community of Indians have lived in Canada since the late 19th century. However, this tiny community - mostly Sikhs in British Columbia - never numbered more than a few thousand, until the latter half of the 20th century.

In 1961, Canada’s Indian community numbered 6,774 (0.03% of the population). In 1967, the Liberal Government of Lester Pearson introduced a new points-based system, designed to liberalise the country’s immigration controls. Ethnic quotas were scrapped, and rules were relaxed for non-European immigration. Later, these rules were liberalised further by the Immigration Act 1976. As a result of these changes, by 1986, Canada’s Indian community had grown to 261,435 (1%).

But this is a far cry from the 1.858 million Indians (5.1%) who were recorded in Canada at the 2021 census - a figure which has grown considerably over the past four years. Between 2013 and 2023, the number of Indians immigrating to Canada annually rose from 32,828 to 139,715, an increase of 326 percent. India is now the single largest source of immigration to Canada, accounting for more than a quarter of all arrivals. So why did Indian migration to Canada spike, and what effect has it had on Canadian society?

This rise has been powered by the increasing number of Indian students at Canadian universities. Indian enrolment at Canadian universities rose by more than 5,800 percent over the last two decades, with 2,181 enrolled in 2000 and 128,928 enrolled in 2021. This is largely the result of Canada’s liberal Post Graduation Work Permits (PGWP) regime, which allows students to automatically seek work in the country following a period of study. In light of political backlash against this policy, PGWP rules were tightened in late 2024, with considerable reductions in the number of student permits issued, and stricter regulations on foreign workers.

Many of these students migrated to Canada fraudulently. In November, the Canadian agency responsible for immigration controls (Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada - IRCC) uncovered over 10,000 fraudulent student acceptance letters, with approximately 80 percent of these fake letters linked to students from the Indian states of Gujarat and Punjab.

Beyond the world of higher education, many Indians have migrated to Canada using the country’s ‘high skilled’ labour route. According to analysis by the National Foundation for American Policy, “highly skilled foreign nationals, including international students, have been choosing Canada over America, because […] it is easy to work in temporary status and acquire permanent residence in Canada.”

This wave of Indian migration has been welcomed by Liberals and Conservatives alike. In 2015, Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper boasted that his Government had taken steps to loosen requirements for Indian immigrants. For Harper, loosening controls on Indian migrants was an integral part of a broader effort to improve relations with Modi’s India. In 2012, he undertook a six-day visit to the country, in an attempt to improve relations; Harper also lobbied to admit the BJP to the International Democrat Union, a global alliance of centre-right political parties.

While geopolitical ties between India and Canada have been frosty under the leadership of Harper’s successor, Justin Trudeau (more on this later), he nevertheless oversaw a marked increase in the level of Indian immigration to Canada.

And has Trudeau’s experiment with ‘highly-skilled’ Indian immigration delivered rewards for Canadians? Not really. On average, South Asians in Canada earn significantly less than white Canadians; indeed, the average after-tax income of South Asians in Canada declined between 2020 and 2022. Labour force participation amongst Hindu and Sikh South Asians is also slightly lower than amongst white Canadians (78 percent versus 73/74 percent respectively).

Though data on this particular metric is difficult to source, there are also numerous reports of nepotism in hiring amongst newly-arrived Indian migrants to Canada. This is a trend shared across all of the Anglophone countries considered for the purposes of this essay; however, given that hard data on ethnic nepotism is difficult to collect, I will only specifically highlight examples which have been subject to legal action.

Whichever way you slice it, Indian immigration has hardly ushered in an economic boom for Canada. In fact, despite the fact that many Indians have used ‘highly skilled’ visa routes to reach the country, hard economic data shows that Indians are slight underperformers. These questionable economic benefits have also been accompanied by significant social and political downsides.

The most obvious example is Canada’s ongoing problem with Sikh nationalism - and the countervailing backlash from Hindu nationalists. According to the 2021 census, 36 percent of Canadian Indians are Sikh - a phenomenon which may have its roots in the fact that Canada’s earliest Indian immigrants were Sikh. Many Canadian Sikhs are supportive of the so-called ‘Khalistan movement’, a Sikh nationalist movement which advocates for an independent Sikh state, incorporating the Indian state of Punjab.

Between 1984 and 1995, supporters of an independent Khalistan led an armed campaign against the Indian government; the most notable episode in this campaign was ‘Operation Blue Star’, during which the Indian Army occupied the Golden Temple in Amritsar, the holiest site in Sikhism, in order to flush out Sikh militants who were hiding there.

The Khalistan campaign was supported by many Canadian Sikhs, who funded and supported Sikh nationalist organisations within India. On June 23, 1985, Sikh nationalists planted a bomb on Air India Flight 182, travelling between Montreal and Mumbai. The bomb killed all 329 occupants of the plane - this remains the deadliest terror attack in Canadian history. The mastermind behind the attack was believed to be Inderjit Singh Reyat, a dual British-Canadian national, and Talwinder Singh Parmar, a Canadian Sikh separatist leader. In many Canadian Sikh communities, Reyat and Parmar remain figures of veneration. The leader of Canada’s left-wing New Democratic Party, Jagmeet Singh, has regularly attended events in the Sikh community where posters celebrating Parmar are prominently displayed.

Understandably, the presence of Khalistani separatists in Canada has led to significant diplomatic tension between Canada and India; indeed, the presence of these groups in Canada has largely characterised the Indo-Canadian relationship over the last few decades.

In 2018, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau visited India in order to attempt to repair ties between the two countries. However, his trip was marred by the revelation that Trudeau’s party included Jaspal Athwal, a Sikh Canadian citizen of Indian origin who had been convicted of trying to assassinate an Indian minister in 1986.

Later in the same year, a proposed Parliamentary motion denouncing “Khalistani extremism and the glorification of individuals who have committed acts of violence to advance the cause of an independent Khalistani state” was dropped following complaints from Sikh activists. In 2019, a report from the Canadian Department of Public Safety was hastily edited following pressure from Sikh activists, after it claimed that “Sikh (Khalistani) Extremism” remained a problem in Canada. Multiple Liberal MPs, including Randeep Sarai, pushed the Department to retract the report - despite considerable evidence of Canadian citizens funding and supporting violent Sikh nationalist organisations.

These tensions boiled over in 2023, when agents of the Indian government killed a prominent Sikh leader, Hardeep Singh Nijjar, on Canadian soil. After the killing, Canada expelled Indian diplomats from the country - India denied all involvement, and retaliated by expelling Canadian diplomats in India. In September 2023, an Indian government spokesman called Canada a “safe haven for terrorists.” In October 2024, Canada expelled six Indian diplomats, including High Commissioner Sanjay Kumar Verma, and declared Verma persona non grata. Canadian officials say that the six expelled Indian diplomats were “directly involved in gathering detailed intelligence on Sikh separatists who were then killed, attacked, or threatened by India’s criminal proxies.” The ordeal has provoked a number of clashes between Hindus and Sikhs on Canadian soil.

The presence of Khalistani groups in Canada, and the outsized political power of the Khalistani lobby, has made it impossible for Canada to conduct normal, self-interested foreign relations with India. This tension has been exacerbated by recent waves of migration from India, which has brought many Hindu Indians - and the Khalistan conflict - onto Canadian shores.

Beyond the Khalistan conflict, Canadian politics and society has been shaped in other ways by recent waves of migration from India. Since 2013, the BJP has operated campaigning branches in Canada, under the moniker ‘Overseas Friends of the BJP’; the RSS operates in Canada, under the name Hindu Swayamsavek Sangh (HSS). Canada’s Hindutva influence network extends well beyond OFBJP - in February 2024, the ‘Hindu Canadian Foundation’ lobbied ten Canadian municipalities to declare January 22nd ‘Ayodhya Ram Mandir Day’, in celebration of the construction of the aforementioned Ram Mandir. In the same vein, the ‘Organization for Hindu Heritage Education’ came to prominence in March 2023, after it lobbied the Toronto District School Board to resist a motion which would enshrine protections against caste-based discrimination.

Groups like these have sought to push Canadian politics in a more pro-India direction. This influence has found an enthusiastic reception amongst the current leadership of the Conservative Party - in June 2023, Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre addressed Hindu voters at the Hindu Sabha Temple in Brampton, Ontario, where he promised to fast-track the immigration process for Indian professionals. In 2023, Deputy Conservative Leader Melissa Lantsman presented a petition to the House of Commons to recognise and define “Hinduphobia” as a specific hate crime in Canada’s Human Rights Code, mirroring the “Islamophobia” language used by many Muslim campaign groups. Lantsman’s petition was supported by a letter to MPs from eighty Hindu-Canadian community groups, spearheaded by the Canadian Organization for Hindu Heritage Education. The petition identified ‘Hinduphobic’ acts such as:

the City of Burnaby commemorating Gauri Lankesh, a vocal critic of Hindu nationalism

the Toronto Star criticising a propaganda film that justifies India’s occupation of Kashmir

an academic giving a talk at a Toronto library about the dangers of Hindu supremacy

Polls indicate that Poilievre’s overtures to Hindu voters appear to have been successful; a May 2024 poll showed that 53 percent of Canadian Hindus intended to support the Conservative Party. However, winning the support of Hindu voters has required the Conservatives to compromise significantly on a range of issues, including freedom of speech, immigration and foreign policy. While Conservatives are right to identify the fact that Hindu voters can be won over by parties of the right, it should also be clear that this support is contingent upon the willingness of those parties to sacrifice principles for short-term electoral gain.

Over the course of the country’s ongoing general election campaign, the Conservative Party has faced significant challenges in managing candidates with ties to Hindu nationalism. Last week, the party was forced to drop its candidate in Etobicoke North, Don Patel, after social media posts emerged of Patel suggesting that Sikh nationalists should be deported to India where Modi can “take care” of them. The Liberal Party has faced similarly challenges - in March, it withdrew support from Chandra Arya, a Liberal MP who has repeatedly criticised the Khalistan movement. Arya has previously faced criticism for raising a saffron flag, traditionally associated with the RSS, on Canada’s Parliament Hill.

In exchange for negligible economic benefits, Canada has imported sectarian conflict, ethnic lobbying, and an ongoing terrorist presence which makes it impossible to conduct normal foreign relations with India. The presence of a large Sikh community in Canada has also prompted the Indian Government to carry out violent attacks on Canadian soil, killing Canadian citizens in an effort to disrupt separatist groups within India. This is hardly a glowing endorsement of the benefits of Indian immigration. While Canadian Conservatives have been able to make some in-roads with Hindu voters, this has required them to make significant compromises on issues such as freedom of speech, foreign policy, and immigration. It is not clear how these compromises benefit ordinary Canadians.

Given the scale and pace of Indian migration to Canada, the Canadian example can serve as a canary in the coal mine - an example of what can happen when migration from India is allowed to take place untrammelled.

India Down Under: Indian immigration to Australia

As in Canada, Australia’s initial experiences of Indian migration are largely the result of the British Empire. However, for most of Australia’s history, the Indian community was relatively small - numbering just 10,319 in 1961-70. This number has ballooned in recent years; at the 2021 census, 783,958 reported having some Indian ancestry, of whom 721,050 were born in India.

This boom in the number of Indians in Australia was first driven by the abolition of the ‘White Australia’ policy, which was conclusively ended by the Whitlam government in 1973. However, even after the end of ‘White Australia’, the number of Indians migrating to Australia remained relatively small, until the 2000s.

The most notable shift occurred in 2006, when the Liberal government of John Howard opened Australia’s doors to Indian students, and introduced policy measures which made it easier for them to get permanent residency. Despite reports of ‘ghost colleges’ and ‘visa factories’, the student route has remained the most popular way for Indians to enter Australia.

India is now the number-one source of immigration to Australia. 92 percent of Indians in Australia were born in India, with more than half arriving over the last ten years. In the year ending June 2022, 43,080 Indians migrated to Australia. In 2023, this rose to 94,840, falling slightly in 2024 to 72,360.

This trend shows little sign of slowing. The Australia-India Migration and Mobility Partnership Agreement, signed in July 2023, provides the following favourable conditions for Indians:

Five-year student visas, with no caps on the number of Indians that can study in Australia

Indian graduates of Australian tertiary institutions can apply to work without visa sponsorship, for up to eight years

The Mobility Arrangement for Talented Early Professionals Scheme allows 3,000 Indian graduates and early career professionals to stay in Australia for up to two years. They can apply for a permanent skilled visa, and spouses have unlimited work rights.

Australian recognition of Indian vocational and university degrees as comparable to Australian qualifications for study and employment purposes

The Partnership Agreement has been followed by a number of other steps which have been taken to liberalise immigration from Australia, including 1,000 special ‘Holiday Maker’ visas for Indians.

This shift has been enthusiastically welcomed by both major parties in Australia, with Prime Ministers from both the Liberal and Labor parties seeking closer ties with India as a counterbalance to China. In 2006, Liberal Prime Minister John Howard conducted a landmark visit to India, where he agreed to liberalise immigration rules for Indian students wishing to migrate to Australia. Howard also opened the door to future Australian uranium sales to Australia. Howard’s successor, Julia Gillard of the Labor Party, followed in his footsteps; in 2011, she lifted Australia’s long-standing ban on exporting uranium to India, conducting a visit to the country in 2012. The Liberal Party’s Tony Abbott has paid particular tribute to the Indian community of Australia, arguing that “India is an emerging superpower and will have a vast role to play globally.”

And more recently, in 2023, Labor Prime Minister Anthony Albanese welcomed Narendra Modi to Australia. At Sydney’s Olympic Park rally, Modi addressed thousands of Indians in Australia - with Albanese serving as his warm-up act, telling the massed crowd that “Prime Minister Modi is the boss.”

The Australian Bureau of Statistics does not reliably publish data on the economic outcomes of different migrant groups - when it does, it tends to group Indian migrants into an “other” category, as opposed to the “major English-speaking country” category used to track the outcomes of migrants from the UK, New Zealand, and the United States. As such, it is difficult to reach useful conclusions about the economic impacts of Indian immigration to Australia - though we can conclude that Australia’s broader experiment with mass migration from the developing world has not been accompanied by a significant increase in the country’s overall GDP per capita.

However, as in Canada, Indian immigration to Australia has been accompanied by a number of social and political downsides.

For one, Australia’s Indian population displays a relatively low level of integration into the broader populace. According to figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, 95 percent of Indians in Australia have children with other Indians - suggesting a low-level of intermarriage and mixing with the broader population. This stands in stark contrast to migrants from Western Europe and North America, the majority of whom are reported as having children with Australian nationals.

Reports of fraud by Indian students at Australian universities are also widespread. According to a 2023 report, some Australian universities report that half or more of their Indian students are either failing to attend classes, or being poached by rival private colleges offering favourable immigration treatment. According to Panjak Pathak, Chair of the Western Australian Private Education and Training Industry Association (WAPETIA):

“Some students are being picked off as they arrive at airports and at bus stops near their universities. Others say that the poachers have close links with the Indian diaspora, finding their targets at temples, in community groups, and in cultural and sporting organisations.”

According to Pathak, 40 percent of Indian students who began studying in Australia in July 2022 had moved on from their original sponsoring institution by the end of the academic year. A 2023 investigation by The Age and Sydney Morning Herald found that five universities had been forced to place bans on Indian students from some states, given the scale of visa fraud amongst would-be Indian students.

As in Canada, Indian immigration to Australia has also been accompanied and encouraged by a network of RSS-affiliated organisations. Both Anthony Albanese and Scott Morrison courted the Indian diaspora at the country’s most recent federal election, attending events hosted by the ‘Hindu Council of Australia’ (HCA). During these events, both men allowed themselves to be draped in scarves of the Vishva Hindu Parishad - a member organisation of the RSS’ Sangh Parivar. In 2021, the HCA condemned NSW Senator David Shoebridge, after he criticised the presence of VHP in New South Wales public schools. Figures associated with VHP Australia were also involved in a brawl with Sikh opponents of Narendra Modi, back in March 2021. More recently, the HCA has lobbied the Parliament of Queensland to introduce new laws on ‘Hinduphobia’, citing criticisms of the RSS and jokes about yoga as examples of Hinduphobia.

The RSS operates directly in Australia, under the Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS) moniker, while the ‘Overseas Friends of the BJP’ also operates a branch in the country. During India’s 2024 General Election campaign, OFBJP hosted rallies in support of the BJP in a number of Australian cities; the group has also vocally condemned efforts to link OFBJP to the Indian Government. In March 2025, the former head of OFBJP Australia was sentenced to forty years in prison, for the rape of five women.

At its most extreme, India’s presence in Australia has posed significant national security risks. In 2020, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) identified a network of Indian Government spies in the country, who were accused of “closely monitoring Indians living [in Australia] and developing close relationships with current and former politicians”. This included attempts to garner information from public servants on security protocols at a major Australian airport and efforts to uncover “sensitive details of defence technology”. Two members of the Indian intelligence agency known as the ‘Research and Analysis Wing’ (RAW) were also expelled from the country in 2020. Unsurprisingly, the HCA slammed these reports as ‘fearmongering’.

Nevertheless, Hindu nationalist lobby groups have been successful in building pro-India sentiment in both of Australia’s major national parties. In March, Liberal leader Peter Dutton pledged AUD$8.5 million to build Australia’s first bespoke Hindu school - a move which was copied by the Labor Party just last week. In November 2023, Dutton undertook a secret trip to India, on the invitation of Prime Minister Narendra Modi - despite criticising Prime Minister Anthony Albanese for taking too many overseas trips. Dutton has been criticised for welcoming Indian immigration; an unearthed 2023 recording features the Liberal leader making the following remarks:

“We’re blessed in this country to have almost - quickly rising - not quite a million but getting towards a million people here of Indian heritage and we’re very fortunate to have them here, and we want the numbers to continue to increase.”

Whether or not Dutton’s overt appeals to the Indian community will bear fruit remains to be seen. However, as in Canada, Australia’s experiment with Indian migration has delivered decidedly mixed results. In exchange for unclear economic benefit, Australians are now lumbered with mass fraud at their universities and ethnic lobbying groups in their politics. Despite the efforts of successive Australian Prime Minister, India still behaves like a hostile power, spying on Australia with impunity and attempting to gain an advantage by infiltrating the Australian civil service.

The emergent pattern of Indian migration to the Anglosphere should now be abundantly clear. Immigration from India has, unfortunately, brought with it low-level sectarian conflict, fraud, and lobbying from RSS-backed organisations, which prioritise perceived ‘Hindu interests’ above all else. This is a far cry from the story of ‘cultural compatibility’ told by many Western conservatives - but should not come as a surprise, given the cultural and geopolitical realities highlighted at the beginning of this essay.

India Down Under II: Indian immigration to New Zealand

While Australia’s experience of Indian migration is characterised by growing closeness with the mainland, New Zealand’s experience has a more uniquely Pacific flavour.

Of the 292,092 Indians recorded in New Zealand in 2023 (5.8% of New Zealand’s population), just 142,920 were born in India; a large proportion of Indians in New Zealand trace their heritage back to Fiji. Indo-Fijians are the descendants of Indian indentured labourers, who arrived in Fiji as a result of deliberate British policy. The passage of Indo-Fijians to New Zealand has mirrored the migration of other Pacific Island groups, over the past few decades. Due to these unique population dynamics, New Zealand’s Indian population is likely to differ from that found in Canada or Australia.

Nevertheless, Indian immigration to New Zealand from India itself has increased dramatically in recent years, in line with the increase in Indian immigration elsewhere in the Anglosphere. Between 2006 and 2013, the number of ethnic Indians in New Zealand increased by 129 percent; between 2013 and 2018, it increased by a further 54%. The proportion of Indian New Zealanders born overseas stands at more than 76 percent, highlighting the fact that this influx has taken place relatively recently. India is now the largest single source of migration to New Zealand, with 51,000 arrivals in the year ending January 2024. In 2023, the number of Indians in New Zealand eclipsed the number of Chinese, for the first time in history.

This change has been driven by a mixture of students, ‘high-skilled’ workers, and family members of existing migrants. The country’s five-year work visa allows migrants to work in New Zealand while pursuing a residence pathway, while the country’s post-study work visa allows tertiary students to remain in New Zealand and work for up to three years after finishing their full-time studies. Under pressure from the Indian community, New Zealand introduced the Culturally Arranged Marriage Visitor Visa in 2019, which allows individuals to travel to New Zealand to marry their New Zealand resident partner under a culturally-arranged marriage. In 2022, New Zealand also reopened the parent category for residence. The parent visa, capped at 2,500 annually, allows citizens or residents to sponsor their foreign parents to gain residency in New Zealand.

However, these routes have also been subject to considerable abuse. In June 2016, Immigration New Zealand uncovered significant, organised fraud amongst immigration agents in India, which included the falsification of bank statements. These agents supported the immigration applications of hundreds of Indian students. In September 2016, one hundred and fifty Indian students studying in New Zealand were deported because they obtained fraudulent visas through agents operating in India. The scale of fraud from Indian applicants was such that, in 2016, just 44 percent of Indian student visa applications were accepted by New Zealand’s immigration authorities, with fraud cited as one of the key drivers behind this low acceptance rate.

In 2018, a Whangarei restauranteur, Gurpreet Singh, was discovered offering Kiwi women as much as NZD$40,000 to marry Indian men, so that they could secure New Zealand visas. Singh was also involved in schemes which charged Indian migrants up to NZD$35,000, in order to help them secure questionable visas and fake jobs. In September 2023, Vikram Madaan was sentenced on eleven counts of immigration fraud; Madaan provided false and misleading information to Immigration New Zealand in a number of work applications, often overstating the real income of the Indian migrants that he hired. In October 2023, a police investigation revealed that Indian migrants were engaged in fraudulently obtaining work visas, through the country’s Accredited Employer Work Visa. The scam required migrants to pay between NZD$20,000 and NZD$40,000 for a job and a visa. Upon arriving in New Zealand, they found that these jobs did not exist; they were subsequently housed in overcrowded properties. The list goes on and on - the reporting of false and misleading information by the sponsors of visas for Indian migrants is widespread in New Zealand. Typically, the culprits are either New Zealand residents of Indian heritage, or immigration agents operating in India itself.

Nevertheless, at first glance, the economic impact of Indian immigration on New Zealand appears largely positive. According to the country’s 2023 census, the median income of Indian adults, at NZ$51,600 is higher than the national average of NZ$41,500, with more than 40 percent of Indians working in managerial or professional jobs.

However, these top-line figures come with significant caveats. In part, these impressive incomes can be attributed to the fact that Indians are significantly more likely to live in New Zealand’s largest cities, where wages - and living costs - are higher. According to the latest census data, 64.7% of Indian New Zealanders live in the Auckland region, where annual household gross income is higher than anywhere else in the country.

There is also the fact that, while Indian migrants enjoy higher average salaries than the New Zealand population as a whole, the country’s overall average is depressed by the country’s large Māori and Pacific Islander populations. When compared to European New Zealanders, Indian migrants actually underperform, particularly when we control for their concentration within high-wage cities like Auckland.

Finally, in light of the widespread fraud outlined earlier in this section, can we really trust official figures on the income of Indians in New Zealand? One of the most common forms of fraud perpetrated by businesses seeking to import Indian labourers is salary overreporting - whereby migrants are hired on the basis of a particular salary, but are, in reality, paid less. Given the large number of high-profile cases uncovered over the last few years, there are significant doubts over whether or not the New Zealand Government’s official estimates of Indian income are actually reflective of the community’s true earnings.

Even beyond the economics, Indian migration has brought with it significant social, cultural, and political challenges. A November 2021 briefing by the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service disclosed that there is “almost certainly a small number of individuals and groups in New Zealand who adhere to Hindutva ideology, motivated by violent extremism”. Organisations such as the Hindu Council of New Zealand, and its youth wing Hindu Youth, are associated directly with the Sangh Parivar - HCNZ’s constitution states outright that the group seeks to imitate the Vishva Hindu Parishad.

Pressure from the Indian Government and its agents has also posed a challenge to New Zealand’s long-standing commitment to freedom of speech. Mohan Dutta, an academic at Massey University, faced criticism from the Indian High Commission in India, after publishing a research paper exploring the ideological roots of Hindutva. The Indian Government has targeted New Zealand-based critics for denaturalisation; in March 2025, Sapna Samant, a prominent critic of the Modi Government, had her Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) visa revoked, for “causing disharmony”.

However, despite the increasing threat of Indian interference in New Zealand’s political and academic arenas, figures from across the political spectrum have embraced Modi’s India and Indian migration. In January 2024, David Seymour (Minister for Regulation) and Melissa Lee (Minister for Economic Development) attended a rally celebrating the opening of the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya. Lee declared that Modi “does very well for the people of India” as she celebrated the temple’s controversial opening, while Seymour declared “Jai Sri Ram”, or “victory to Lord Ram”, in his supportive remarks.

As mentioned previously, the opening of the Ram Mandir marks a significant ideological victory for the Hindutva movement in India. Following the mob-led demolition of the Babri Masjid, which stood on the site from 1529 until 1992, Hindu nationalists have long coveted the site for the construction of a new temple. The appearance of two senior New Zealand Government ministers at an event celebrating the temple’s opening shows the extent to which Hindutva’s growing influence is shaping New Zealand politics.

In March, Prime Minister Christopher Luxon conducted a high-profile visit to India, aiming to strengthen ties and foster bilateral trade. The two countries have committed to resuming free trade negotiations, while Air New Zealand and Air India have announced plans to run direct flights between the two countries by 2025. Luxon also touted the New Zealand Excellence Awards (NZEA), a new scheme designed to offer scholarships to Indian students at top New Zealand universities.

Despite pledging to tighten visa rules amidst ‘unsustainable’ migration, Luxon’s government has taken steps to loosen rules for ‘high skilled’ migrants. Major work visa changes, which began in March 2025, will simplify the hiring process for employers and relax requirements for prospective workers, including reducing work experience requirements and offering longer visa durations. All of this will make New Zealand a more accessible destination for Indian immigrants.

Amidst mass fraud, and political interference from the country’s Indian High Commission, New Zealand politicians still advocate for closer relations with Modi’s India and an intensified policy of migration from India. As in Australia and Canada, this approach is short-sighted and careless. Does this really serve the interests of ordinary New Zealanders?

Viparyaya: Indian immigration to the United Kingdom

Of all the Anglosphere nations, Britain has the longest and most complicated history of Indian immigration.

Throughout Britain’s centuries-long rule in the Indian subcontinent, a very small number of Indians travelled to the UK, mostly as businessmen and sailors. However, Britain’s Indian population remained negligible until the 1960s. In 1931, an estimated 10,186 Indians lived in the UK, rising to 31,000 by 1951, and to 81,000 by 1961. In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, Indian immigration increased, enabled by the British Nationality Act 1948, which enabled migration from the Commonwealth with very few limits. Britain’s post-war Indian migrants were largely from Bengal, Punjab, and Gujarat; they were often employed as factory or textile workers, settling in places like Leicester and West London. The Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 and Immigration Act 1971 largely restricted any further large-scale settlement, though family members of already-settled migrants were still allowed to apply for settlement.

However, by 1971, the number of Indians in the UK had increased to 375,000, an almost-fivefold increase. By 1981, this population nearly doubled, to around 676,000. This sudden increase was driven by two factors. First, at that time, Indians in Britain had more significantly children than average, leading to a natural increase in the overall Indian population.